PAGE 125

It was traditional for their wives…

Some of them made an appearance on the BBC Woman’s Hour programme, although I have not been able to find a record of what they said.

Jessy Edrich (Bill’s third wife – he was not selected for the tour), Jean Evans, the Woman’s Hour presenter Jean Metcalfe, Dorothy Hutton and Greta Bailey.

The next year, before the tour of Australia, wives definitely complained about not being invited to the farewell dinner (Daily Mail, 15 September 1954).

According to Percy Fender, Australia was known as ‘the divorce tour’ in the 1920s, when it could last eight months (Marshall, Gentlemen and Players, p.101). The pros and cons of wives on tour was a traditional debating point, and is discussed further in Chapter 16.

Sir Walter Monckton, the Minister for Labour

In Ball of Fire (p.50) and As It Was (p.148), Trueman says that the government figure who attended the dinner was ‘Lennox-Boyd, who was the Colonial Secretary then’. Almost certainly he has been let down by his memory, or his ghostwriters, because Lennox-Boyd did not replace Oliver Lyttelton as Colonial Secretary until July 1954. One report states Lyttleton was the speaker, but most, including Hutton (p.94) and Compton (p.110), remember it being Monckton, who is the most likely candidate given his MCC connections. Lord Cobham, MCC president, presided over the toasts the next winter before the tour of Australia.

Monckton had kept wicket for Harrow against Eton in ‘Fowler’s Match’ of 1911. He did not win a Blue at Cambridge, but played in one first-class match for a Combined Varsity side against the Army and Navy, scoring 43 and 29* at number eleven and thus securing a career batting average of 72. He continued to keep wicket for the Bar into his fifties. When his political workload allowed, he enjoyed his involvement with Surrey and MCC. Jack Hobbs is reputed to have turned to Monckton in an attempt to avoid being knighted in the Coronation Honours List (Williams 2012, p.36). That year, Monckton gave a speech at an Oval reception for the Australians during their county game against Surrey (Fingleton 1953, p.59). Monckton succeeded another old Harrovian, Lord Alexander of Tunis, as MCC president in 1956. His second wife, Bridget Hore-Ruthven, was the niece of Lord Gowrie, another MCC president.

‘a band of pinkos’

No less an authority than E.W. Swanton is the source for this quotation (Barclays World of Cricket, p.51).

Despite serving in several Conservative governments, Monckton never joined the party. In Eminent Churchillians, Andrew Roberts gives a rather spiteful character sketch of Monckton, explaining why Churchill never trusted him because of the ‘pinkness of his views’ (p.249). Monckton’s card was also marked by the Prime Minister because of his friendship with Stafford Cripps (a man Churchill used to call Stifford Crapps) and because of his role as advisor to Edward VIII during the Abdication Crisis. However, Peter Hennessy suggests that Churchill’s choice of Monckton for the sensitive role of dealing with ‘the trade-union question’ was a wily political move, and cites Rab Butler recognising that Monckton’s ‘serene non-political outlook produced all the effects Churchill hoped for from his appointment’ (Having it so Good, pp.198-99).

‘wore himself out by giving way’

In the two days immediately after the MCC dinner, Monckton was involved in a round of strenuous negotiations with the rail unions and their employers. Once the strike was averted, he admitted himself to hospital in January suffering from exhaustion, eczema and gout.

Monckton appears very briefly in this Movietone report on the suspension of the strike.

Moss remembers…

Interview with author, 31 March 2015.

One suspects Monckton’s speech may have been similar in tenor to the one Laker recalled before the 1956/57 South Africa tour: ‘Before we left England, we were given the usual preliminary briefing by the President of MCC. He reminded us of South Africa’s problems, and told us that colour, as a topic of conversation, was strictly out. It was something never to be mentioned’ (Over to Me, pp.90-91).

‘It was pointed out that the political situation…’

Compton, End of an Innings, p.110.

PAGE 126

‘excellent as far as it went…’

Hutton, Fifty Years in Cricket, p.95.

£500 (pre-tax) plus a £50 good conduct bonus

In Ball of Fire, Trueman says he was expecting £200 after tax and in As It Was that his efforts on tour would be ‘all for £750’ (p.148). In fact, the players’ contract states that their remuneration was £500 (£50 to be paid before departure, £200 on tour and ‘the balance on conclusion of the tour on arrival in England’) plus the good-conduct bonus of ‘not more’ than £50.

Using the Bank of England’s calculator, £500 in 1953 would equate to £14,276 in 2020 (average rate of inflation 5.1%).

Although cricketers’ salaries increased in the 1950s, they did not do so in inflation-adjusted terms: a capped professional was on average earning between £700 and £800 per season in the early 1950s (see Down, p.48).

In 1956, Willie Watson calculated the annual wages of an ‘average’ footballer with a good club in mid-table as just under £800 (Double International, p.111)

‘So I upped and said…’

Trueman, As It Was, p. 148. For a slightly less dramatic version, see Ball of Fire, p.50.

‘not adequately briefed’ … ‘either by the government or by MCC’

More Than Just a Gentleman, p.85.

On his return, Palmer made a formal recommendation to the MCC Cricket Sub-Committee that before future tours England players should receive ‘a more detailed briefing concerning conditions in the country they were visiting’ (Minute 5 (a), 25 May 1954).

a more difficult political situation

An article in The Listener, volume 51, issue 1315 (13 May 1954) described the atmosphere in the West Indies as ‘delicate’.

One could also draw analogies with the tours to India led by Gower in 1984/85 (when Indira Gandhi was assassinated just after the team arrived) and by Pietersen in 1997/98 (when the team briefly left India for Dubai after terrorist attacks in Mumbai); the difference is that these tours were suddenly made difficult by a specific unforeseen event, whereas MCC sent Hutton’s men to the West Indies in the knowledge that the British government had recently suspended the constitution of British Guiana, one of the Test venues.

preparatory breathing space

See Palmer’s letter to Hutton on Leicestershire CCC headed paper, dated 11 November 1953, which is reproduced in the book: ‘I do think this flying over to the West Indies is a snag in many ways because it means that we are catapulted into the activity of the tour without that valuable breathing space when we can get among the side and sort out one or two preliminary matters.’ It was generally agreed, in spite of occasional evidence to the contrary, that passages by boat helped bond touring teams together: Warner give a talk in 1946 advising travel by boat not by air for this reason (Howat, p.205).

the roles of scorer and baggageman, usually combined by…Bill Ferguson

Ferguson had made a virtual monopoly of the job of scorer/baggageman, both for tourists to England and for overseas tours, whether by MCC or other international sides.

On West Indies’ tour to Australia in 1951/52, he was described by the journalist Harold Dale as ‘a unique figure in the cricket world’, who had ‘advanced the handling of baggage and the scoring of cricket to a height of technique never before known’ (Cricket Crusaders, p.20). One of his innovations was to draw up what would now be called ‘wagon wheels’ for each Test batsman, which he claims became ‘world famous’ (Mr Cricket, p.170).

It was almost certainly the case that the West Indies Board of Control budget did not stretch to a dedicated scorer/baggageman, just as it did not stretch to a masseur (to the disappointment of Hutton and Bailey who wanted to bring the Essex masseur Harold Dalton – see Chapters 16 and 18). But, while Ferguson’s failing health may also have been a factor, there is a possibility that MCC, or Hutton, did not want him in the party anyway. Ferguson scored the Coronation Ashes, and South Africa’s tour to Australia the winter before, but he makes some bitter remarks in his memoirs about being ‘sacked’ for the 1954/55 Ashes tour (pp.58-59). See Chapter 18 for further observations.

PAGE 127

the first surprises were that Compton…

This is reported by Bannister, who noted that Compton’s tardiness was a feature of his ‘distinguished’ career: ‘His familiarity with the running-boards of trains gathering speed and the hoisting gangplank bordered on something out of this world. Yet here was the same Denis, bright and shining, first to reach Heathrow and with oceans of time to spare’ (Cricket Cauldron, p.16). According to Bannister, Palmer – who probably knew Compton’s ways well, having played with him in India during the war and toured with him to South Africa – asked ‘Is my journey really necessary?’

For affectionate tales of Compton’s forgetfulness, see Blofeld, Cricket and All That, pp.148-49.

Hutton had made four long plane journeys on MCC duty

After the 1946/47 tour to Australia, Hutton flew home to England with some of the journalists, ‘becoming the first professional cricketer to return from an Australian tour by air’ (Howat, p.72). He was flown out to British Guiana, via Lisbon, Dakar and Brazil, as an emergency replacement in 1947/48 (p.75). After the final Test in Jamaica, he flew home via Nassau and New York, ‘where a magnificent ham in his luggage was excused customs duty when he was described to the Americans – for the first, but not the last, time – as the “Babe Ruth of English cricket”’ (p.76). For the next Australian tour most of the team flew back to London via Fiji, Honolulu, San Francisco, Chicago and New York (p.99).

Albert Sylvester, who after Hutton’s retirement from cricket worked with him at the Hull firm J.H. Fenner, observed that ‘he hated flying but he did it’ (Len Hutton Remembered, p.178).

‘something entirely new’

May, A Game Enjoyed, p.51: ‘This was a great experience for me. I had been on a Butterflies tour to Germany. I had been vice-captain of the Cambridge soccer team in Greece. I had been to Switzerland with Pegasus. But that was the extent of my overseas travel, and the flight to Bermuda and the stay there were something entirely new.’

Trueman, as an ‘RAF type’, had flown before, but the ‘luxury Stratocruiser’ was nevertheless ‘a big thrill’ (Fast Fury, p.78).

James Bond’s airliner of choice

See Parker, Goldeneye, p.93 for Fleming’s preference for Stratocruisers when flying to Jamaica. Bruce Allen’s website gives some colour on Bond’s three Stratocruiser flights (and a picture of the cocktail bar).

Because the Royal Yacht Britannia was not quite ready at the start of the 173-day Coronation tour of the Commonwealth, the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh had flown to Bermuda on an especially furnished BOAC Stratocruiser, Canopus.

Moss remembers…

Interview with the author, 31 March 2015.

‘quite a to-do’

Miller, Charles Palmer, p.85.

‘Though there is no cause for alarm…’

Trueman, As It Was, p.151.

Earlier in 1953…; in 1954…

On 2 February 1953, an old Avro-York four-piston airliner disappeared over the Atlantic on its way to Kingston via Gander in Newfoundland. It was carrying 6 crew and 33 passengers, mostly soldiers and their families bound for a tour of duty in Jamaica. On Christmas Day 1954, a 377 Stratocruiser crash-landed at Prestwick, killing 28 of its 36 occupants.

Long journeys in piston-engined aeroplanes were certainly not without risk in the 1950s. When Compton flew out late to Australia in 1954, after having extra treatment on his knee, his plane was forced to crash-land in Karachi. The Munich air crash of 1958, where eight Manchester United players were among the dead, is of course the most infamous disaster involving sportsmen: according to Stephen Chalke MCC decided after this that its tour parties should be split up and travel on two different aeroplanes (Through the Remembered Gate, p.97).

Gander in Newfoundland

The MCC’s plane may have been scheduled to refuel there in any case, like the ill-fated Avro-York. On the next tour MCC also transited there, Alan Ross sharing a room with Swanton, whom he remembered slumbering ‘on his bunk, a sultan islanded in sleep’ (Through the Caribbean, p.13).

‘light summer suitings’

For Surrey and England, p.55: ‘In Gander we had no negotiable currency – Canadian dollars were the legal tender there – and we had to put on what charm we could to persuade the girl behind the stall that we badly needed sustenance. I fear “our charm” smiles must have been frozen, but the girl took pity on us, and, in any case, someone provided the necessary money and we drank piping hot coffee. That was just about the best coffee I have ever put down.’

Trueman had also changed into ‘tropical clothing’ (Fast Fury, p.78) – quite why they didn’t change back again when they learnt of the detour is unclear.

Trueman found himself standing next to the Duke of Gloucester…

As it Was, p.151-52.

Supposedly, the chef asked Gloucester whether he preferred his eggs sunny-side up and, when informed of his guest’s identity, exclaimed ‘Gee, a real live Dook? Like John Wayne?’ As so often with Trueman, it is easy to be sceptical, but there were definitely other passengers on the flight, including the Jamaican batsman Ken Rickards, who was hoping to stake a claim in the Test side.

Palmer roomed with Trueman, Hutton with Moss

Moss, interview with the author, 31 March 2015.

One tourist, possibly Wardle, became inconsolable…

Bannister tells this story, which again is possibly over-embellished: the player in question had ‘with bulldog persistence … filled in the same permutation week in week out for ten years’; although a Newfoundland postal official sent his coupon off five days before the relevant Saturday, it did not arrive in time and – inevitably – the player’s lines would have won him £25 (Cricket Cauldron, pp.16-17).

PAGE 129

‘most anxious’ … ‘en route to the West Indies’

MCC Committee, 9 March 1953, Minute 4c.

Robins, who had played on Julian Cahn’s tour to Bermuda in 1933…

According to Robins’ biographer, Brian Rendall (p.52), the tourists’ match against Somerset CC in 1933 was the first time an English team had played a multiracial game in Bermuda. Bannister recounts the story of a most exciting finish: ‘George Heane [Notts captain] took a brilliant catch in front of the sight screen from a ball which looked to be sailing for six. Sir Julian Cahn’s team won by three runs – to the undisguised relief of the Northumberland Fusiliers stationed on the island who had taken heavy bets on his team at odds of three to one’ (Cricket Cauldron, p.19).

Stanhope Joel, the South African diamond magnate

The Joels hailed from Spitalfields but I think it is fair to describe them as South African in the sense that Solomon ‘Solly’ Joel went there to make the family fortune by developing a diamond cartel. His watchword was ‘as long as women are born, diamonds will be worn’ (Ace of Diamonds, p.68).

Stanhope wrote a biography of his father Solly, which makes passing reference to ‘his subsidization of cricket and sports in general’ (p.213). The Joels were most famous as racehorse owners and breeders, but Solly sponsored a significant tour by English cricketers to South Africa in 1924/25 and, like another Jewish businessman Julian Cahn, took a keen interest in country-house cricket: the Tennysons, the Gilligans and Percy Fender seem to have been part of his circle. In 1927, Solly donated £10,000 and 20 acres of his Reading estate to the National Playing Fields Association – the Duke of York opened the Solomon Joel Playing Field in July that year.

Stanhope continued the family traditions, although his own interest in competitive sailing may be one reason why he spent most of his time in Bermuda (another must be tax avoidance). He may have offered to underwrite MCC’s visit to ingratiate himself with the country-house set, and/or he had a genuine interest in developing local cricket, identifying with the black cricket clubs because of the prejudice he no doubt encountered on the island himself. Or he may simply have written the cheques and not asked many questions. His motivations are fascinating, but very difficult to recover.

Joel is pictured below, on the point of his emigration to Bermuda in 1950, with his daughter Thalia and his wife Gladys.

agreed to underwrite MCC’s expenses in Bermuda

According to Bannister (p.21), the island’s Trade Development Board paid the extra cost of MCC’s air-fares to Bermuda (£2,000) and Joel, ‘who is reputed to enjoy a tax-free income of £130,000 a year’, picked up the tab for ‘hotel costs and other incidentals’ (about £1,500). It seems there was little defrayal of these expenses by gate receipts. Compton says the experimental trip to Bermuda was ‘an utter financial flop’ (p.111); Wardle assumed ‘a good deal of money was lost on the venture’ (p.121).

supervising the removal of the permanent army garrison

It was announced in 1951 that the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda would be closed, that the naval base would be slowly run down over the next decade and that the regular army garrison would be withdrawn by 1953. Churchill had second thoughts after the summit that year – but 1957 was the last year a British regiment would be stationed on the island.

where Eisenhower privately told Churchill…

See Ruane and Jones, Anthony Eden, Anglo-American Relations and the 1954 Indochina Crisis. The summit was of the ‘Big Three’ powers, but the French Premier Joseph Laniel fell ill in Bermuda and so the spotlight fell even more on the Big Two.

Monckton’s pre-tour lecture does not seem to have extended…

This is certainly the impression given by Palmer, who says he ‘hadn’t been told about’ the colour bar on the island (Miller, p.85).

But, shortly before departure, Hutton was quoted by the Bradford Observer as saying the situation in Bermuda was ‘rather unique’ (1 December 1953), so perhaps its colour bar had been mentioned to him by Monckton or another MCC figure.

modelled on the southern states of America

The Bermudan colour bar came as a shock to those West Indian migrants who sometimes had to stop over there on their way to Britain. One remembered being told to sit in a separate part of a cinema, and getting into a fight when he refused to do so (Phillips and Phillips 1998, p.64), another that racial segregation on the island was ‘rough’ (Grover 2018, p.193).

Schools and theatres were segregated and, although black boys were allowed to play at one of the tennis clubs in after the war, they were allowed to use only the outside toilets. As this Bermemes documentary outlines, matters came to a head in a black boycott of such venues in 1959.

‘And then people started semaphoring…’

Miller, Charles Palmer, p.85.

PAGE 130

the many Guyanese who saw Sir Frank as a ‘local white’

Frank Birbalsingh used this expression in his interview with the author, 20 June 2018: when he was growing up in British Guiana, his impression was that McDavid was the most powerful figure in the local establishment.

One of the MI5 files on the nationalist leader Cheddi Jagan records his reference to ‘stooges like McDavid’ (Kew National Archives, KV-2-3606, p.55).

a protest by the black members of Bermuda’s parliament

There were only six such members in 1953: they wrote a letter to the Governor about the McDavid incident. This seemed to have as little tangible effect as the report of the Bermudan Parliamentary Select Committee on Race Relations, published in January 1954, which noted that segregation was normal practice in both the public and private sectors.

‘at certain hotels’ in Bermuda

Lyttleton’s exchange with the Labour MP Tom Driberg, on 9 December 1953, is recorded in Hansard, volume 521 cc238-39W. The minister explained he had ‘conveyed his regrets’ to McDavid when the incident was originally reported in July but that a pragmatic approach had to be taken: ‘Her Majesty’s Government have always been strongly opposed to the colour bar, but I am advised that its maintenance in certain hotels in Bermuda is essential to the tourist trade on which the people of the Colony as a whole depend for their livelihood.’

‘threatened the undoing of the British Empire’

Blake made this observation in the December 1953 issue of Spotlight magazine (quoted in Goldeneye, p. 103).

Blake was already famous for making a protest against the more informal colour bars which prevailed in the luxury hotels in Montego Bay: in 1948 he had jumped into the swimming pool of the Myrtle Bank Hotel. According to some reports, white swimmers immediately jumped out, and the pool was drained and cleaned before it was used again. The hotel then gave Blake a lifetime member’s pass, which rather proved his point that entry to many hotels was beyond the means of black Jamaicans.

Evon Blake (photo from National Library of Jamaica website)

the Daily Herald having already taken Governor Hood to task

The Herald (25 Nov 1953, p.6) not only berated the Governor for his ‘gross ill manners’ but also pointed out that the itinerary of the Queen’s tour included several colonies, such as Jamaica, Fiji and Uganda, as well as the Dominion of Ceylon, which had ‘coloured’ majorities: ‘They help to make up 500 millions who wish to remain members of the Commonwealth, only on a genuine basis of equality.’

On the same day, the Daily Mirror, under a headline NO, NO, NO, demanded an end to the ‘blind snobbery’ of the colour bar: ‘Will our officials never learn? She is journeying to meet her peoples in the name of this awakening Commonwealth. Let her.’ Photographers had been barred when the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh, in their last official function on the island, attended a State dinner at Government House, which about 30 of Bermuda’s leading white officials and dignitaries attended.

Constantine also makes reference to this incident in Colour Bar (p.190): ‘We know why none of us was invited – not only Bermudans know it, but coloured people in every part of the world. Such distinctions are never forgotten.’

Even though the local Board of Control was by now ostensibly multi-racial

Frank Manning, in the 1981 article alluded to below, asserted that ‘when racial integration was nominally introduced in the 1960s, whites virtually withdrew from the game’ (‘celebrating cricket’, p.618).

According to Calvin Symonds, one of the best black players from the island in the period, the white Bermuda Cricket Association League and the black Somers Isles League kept entirely separate and had ‘separate Boards of Control’ until the 1960s (Zoom interview with author, 15 May 2021). It seems certain that a colour bar essentially prevailed in cricket until then.

However, while references to Bermudan cricket administration are frustratingly vague in the reports on MCC’s visit, it does seem that there was some kind of superficial attempt at a multiracial Board of Control, even if, reading between the lines, the Bermuda Cricket Association took little interest in the MCC tour once it was decided that the games would be played on a Somers Isles ground. As with Joel’s role, I have found it impossible to get to the bottom of the matter, especially as the Bermuda Cricket Board confirmed it has ‘no records dating back that far’ (e-mail from Samantha Robinson to author, 24 January 2018).

‘Cup Match’ had its roots as a carnival

In a piece of fieldwork influenced by the approach of Clifford Geertz, the Bostonian social anthropologist Frank Manning wrote an article for the American Ethnologist claiming that Cup Match was Bermuda’s biggest festival outside of Christmas, and proposed that its carnivalesque rituals ‘symbolically depict both a reflexive, assertive sense of black culture and a stark awareness of black economic dependency on whites – a dramatic tension that is also the semantic context of Bermudian politics’ (‘Celebrating Cricket’, p.616).

‘the one truly spontaneous holiday’

Eva Hodgson, pp.38-39: ‘Cup Match was a day when Negroes protested against their bondage by throwing off all care for two days. The Cup Match was the one truly spontaneous holiday for the people by all of the people of Bermuda. It was then, as now, the one and only true symbol of the black man’s Emancipation. Those two days of cricket, held on Emancipation Day, and springing originally from the picnics of the Friendly Societies remain, today, an event of moment in the lives of Bermudian Negroes.’

a ‘Pick of the Leagues’ featuring six white players

Mulder, the fast bowler who dismissed Hutton, was one of them. Calvin Symonds says he only knew of Mulder by reputation, as he never played with or against him because of the de facto colour bar. Symonds had to sit out the first game to make way for the Bermuda Cricket Association contingent.

ascribed to a variety of factors

See Bannister, Cricket Cauldron, p.20; Compton, End of an Innings, p.110-11.

PAGE 131

hinted that ‘discrimination’ was a factor

Woldo Sommons, the ‘coloured’ chairman of Somerset CC, quoted in a report by Rostron in the Daily Express: ‘Coloured supporters of the game will face this loss as best they can. I get along with whites – that is why I am president of the Board of Control – but there is discrimination.’

In the same report, Jim Murray, described as the white secretary of the Board, was quoted as saying ‘the poor support of the MCC game was merely because of bad weather and the inaccessible ground’. Bannister noted ‘local differences’ in Bermuda, but seemed to misunderstand how the ‘two leagues’ were constituted (Cricket Cauldron, p.20).

‘a total boycott of play by ninety-nine per cent of Europeans…’

Compton, End of an Innings, p.110.

‘Of course there is some kind of colour bar in Bermuda…’

Evans, Action in Cricket, p.77.

the exclusive Mid Ocean Club

Eva Hodgson records that in the 1960s black Bermudan MPs boycotted a Speaker’s Dinner at the Mid-Ocean Club because they considered it a ‘locus of infection’: in their view the Club ‘is even more prone to a policy of exclusion than any of the Hotels, it is even doubtful if persons of colour can even be guests of members of the Mid-Ocean club in ordinary circumstances’ (p.228).

Wardle and Spooner had difficulty…

Wardle remembered Spooner had already put one ball in the lake guarding one of the par-threes before deciding to move to the ladies’ tee: ‘Solemnly Dick teed up; slowly and with great dignity his ball rose and plopped into the lake. I laughed so much that with my next shot I took a tremendous slice, straight over mid-off, and landed the ball in the lake beside Dick’s’ (Happy Go Johnny, p.120).

Compton and Palmer with the amount of alcohol…

Bannister may be hamming things up when he recounts the consumption of the home pair playing Compton and Palmer:

-

- 5 gin and tonics before lunch

- more gin and tonic, with beer, over lunch

- Van Der Hum liqueur after lunch

- gin and tonic on second hole

- a bottle of Van Der Hum emptied between holes 3 and 9

- 3 gin and tonics in the clubhouse at the turn

- A gin and tonic produced by the caddy for the tenth hole

- A bottle of brandy uncorked on the eleventh hole and finished by the sixteenth

The MCC pair won the match on that hole. Bannister may now be playing things down: ‘From time to time they had been pressed to share the refreshment but surreptitiously they emptied theirs into bunkers, the rough and behind bushes’ (Cricket Cauldron, pp.22-23).

Governor Hood had won the premier amateur matchplay tournament…

The Jubilee Vase – Hood beat B.H. Thomson by two holes in the final.

It seems Hood timed his visits back to Britain so that he could take part in the big amateur tournaments at St Andrews. In 1954, he participated in the Calcutta Cup in a pair with Lord Aberdare (they beat Sir John Somerville and Major-General W.B.H. Mirrlees 3 and 1, but went out in the second round).

Graveney, the best golfer in the party…

An article on Ken Suttle in the Worthing Herald (19 March 1954, p.20), drawing on one of his letters home, usefully provides the current handicaps of some of the England players: Graveney 1, Hutton 5, Evans, Compton and Suttle 8, Palmer 14. I will guess Laker was also a sub-20 handicapper.

‘a whale of a time’

Graveney, Cricket through the Covers, p.111.

‘Our menu that night included pâté de foie gras…’

Statham, Cricket Merry-Go-Round, p.87

‘the astonishing sight of Errol Flynn consuming…’

Bailey, Wickets, Catches and the Odd Run, p.187.

similar advantage of the amenities

Wardle described Stanhope’s function as ‘the sort of party that made you think of Aladdin and his wonderful lamp’. He was one of six MCC players taken for a sight-seeing tour on Stanhope’s speed-boat, during which Trueman, who had forgotten his swimming trunks, also lost his underpants after ‘a beautiful swallow-dive’ (p.122).

One imagines Wardle making the most of the party, given his well-known parsimony and his complaints about the cost of living in Bermuda: ‘If you wanted a steak for dinner, it cost an extra 28s., on top of the £2 you were already paying for the meal. It made a Yorkshireman feel thankful that the hotel bills weren’t being paid out of his own pocket’ (p.119). Lock was another to be thankful that Stanhope was paying expenses given the ‘sky-high’ prices on the island. Bannister, whose expense allowance from the Mail was presumably more frugal, was shocked to learn from Bailey that the hotel charge for shoe-cleaning was 3s. 6d. Statham found Bermuda ‘a terribly expensive’ place: ‘We had an outstanding experience of how the rich live’ (p.87).

…a list of ducks on debut…

Second XI debut

24 May 1933 – Yorkshire 2nd XI v Cheshire: c Tipping b Burgess 0

‘Hutton hung his bat at a rising ball from Burgess and was deservedly caught at slip’ (Yorkshire Post)

Second XI Roses debut

6 June 1933 – Yorkshire 2nd XI v Lancashire: b Higson 0

‘Hutton, the young Pudsey batsman, appeared convinced that it was a four-day match, and for 25 minutes he remained a monument of caution before he was dismissed – without scoring!’ (Yorkshire Post)

First-class debut

2 May 1934 – Yorkshire v Cambridge University: run out 0

‘It is a long distance from wicket to pavilion at Fenners, especially when you have failed to score, and on this day the pavilion steps seemed further away than ever. Eventually I reached the dressing room, where Maurice Leyland consoled me with the words, “never mind, Len, you’ve started at the bottom”’ (from a 1941 Hutton radio broadcast).

Test debut

26 June 1937 – England v New Zealand: b Cowie 0

‘On this occasion I would have dearly loved to return to the Pavilion by tube. The same evening, trying to take my mind off cricket, I visited the Cinema, only to see myself in the News Reel return to the Pavilion a sadder but wiser man’ (same broadcast).

First war-time game as captain of Pudsey St Lawrence

24 April 1943 St Lawrence v Bankfoot: bowled 0

‘The duck I made was nothing compared with the grand fact I was playing again’ (quoted in Howat’s biography).

PAGE 132

‘pointless’ from a cricketing point of view

Cricket through the Covers, p.111: ‘As regards batting practice, the matches were pointless for the ball bounced an unnatural height from the matting-on-concrete wickets’.

Although the stay in Bermuda was a ‘pleasant interlude’ and helped the players acclimatise, Graveney found all three games ‘of little value from our point of view’. He also remembered an incident when May, who records in his own memoirs that he found the practice games ‘a little unreal’ (p.52), hit a six into the miniature cliff-face on one side of the Somerset ground: ‘The umpire would not be convinced that the ball had come off the wall and allowed only one run!’ (Heart of Cricket, p.41). Bannister corroborates (although it may be Graveney’s ghost was relying on Bannister – the consumption of Compton and Palmer’s golf partners is recounted at some length).

Calvin Symonds (Zoom interview with author, 15 May 2021) could not remember the May incident, pointing out it may have occurred in the first game in which he did not play, but does confirm that the matting wicket at Somerset generated unnatural bounce and turn. He still thinks MCC took the games ‘seriously’ as a way of acclimatising for Jamaica.

‘for the benefit of spreading the gospel…’

Bailey, Wickets, Catches and the Odd Run, p.187.

Trueman…felt this adjustment affected the rhythm of his run-up

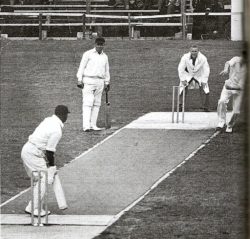

There is a surviving photograph of Trueman bowling well wide of the strip, and Calvin Symonds remembers that the Bermuda side gave their permission for him to do so without being no-balled.

In fairness to Trueman, never slow to make excuses for himself, the fast bowler’s occupational hazard of the impact of pitches on his feet had been one of his ongoing problems. See the 1953 Wisden’s Cricketer of the Year essay:

During the 1952 season, Trueman was frequently no-balled by the umpires for ‘dragging’. He had difficulty in getting boots able to take the strain imposed on them. He sprained an ankle when playing for the RAF, and during the Test Matches at Manchester and The Oval he showed a distressing tendency to get ‘stitch’. These troubles have mostly been cleared. Special boots have been made; the ankle injury was due to a bad foothold; and the ‘stitch’ was diagnosed as nothing more than a lack of regular fast bowling exercise.

As we shall see in Chapter 9, Trueman suffered from heel problems in Jamaica and had to change his boots during the first Test.

‘The spectacle of seeing a star England bowler…’

Report by Thomas Aitchison in Bermuda Sports, February 1954 edition.

Calvin Symonds does not remember Trueman saying anything to him while he was batting, but some of his teammates reported they did get an earful from the Yorkshireman.

‘homely seasonal atmosphere’

For Surrey and England, p.58: ‘On Christmas Day, the boys were invited to spend the day with various families in the district. This created a homely seasonal atmosphere which could not be achieved in a hotel.’ Lock celebrated his birthday while in Bermuda: ‘It was an enjoyable period; hospitality was excellent, and even included a visit to a Royal Navy destroyer that was in port’ (pp.55-56).

Another highpoint, according to Wardle, was a trip to the Bermuda Aquarium. His autobiography gives an almost lyrical account of his stay, perhaps reflecting the input of his ghostwriter A.A. Thomson. See, for example, the account of the street-dancers who fascinated Wardle when Bermuda celebrated Boxing Day ‘from dawn till midnight’: ‘These entertainers are called Gombeys, a group of coloured dancers who display a mixture of West Indian and African tribal rituals; the dances are in fact a series of mumming plays, accompanied by drums, flutes and voices, and are distantly descended from the London street-plays of the twelfth century’ (pp. 121-22).

a ‘dreadful Christmas Day dinner…’ … ‘a dragon straight out of Oscar Wilde’

Bailey, Wickets, Catches and the Odd Run, p.187.